As was customary in the United States, the educational innovations advocated by Helen Parkhurst were named after one of the places where she first experimented with them: the town of Dalton in Massachusetts.

An organizational-didactic revitalization

Parkhurst’s Dalton Laboratory Plan is primarily an organizational-didactic, curriculum-neutral educational concept with the aim of “revitalizing” the school procedures used in education. Parkhurst did not build a new educational concept from scratch, but wanted to revitalize an existing educational system that had all the characteristics of lock-step teaching.

In her 1922 book Education on the Dalton Plan, Parkhurst describes a number of basic ideas for a modest innovation: innovative, because it capitalizes on the entrepreneurship and personal responsibility of students (Van der Ploeg, 2010). She wants to revitalize education, breathe new life into the ‘old school’, by turning it into a living ‘something’ that is capable of arousing and maintaining students’ interest in their work. She enables students to learn at their own pace: “(…) for only so can the work be assimilated thoroughly” (Parkhurst, 1922, p. 37).

Parkhurst states in her book that she cannot change everything at once. Realistically, she says: “I offer it (the Dalton Laboratory Plan) as a first step towards the evolution of a scheme of education which will develop the creative faculty in both teachers and pupils. I have been animated in elaborating it by a desire to remedy some of the ills our schools are heirs to, and especially the worst of these, which is, I believe, the absence of opportunity for the learner to learn” (Parkhurst, 1922, p. 173).

Her focus is on ‘a way of life for children’ (Luke n.d.), whereby any curriculum can be used for the time being.

“At the moment, however, I shall confine my observations to its application as an efficiency measure involving both academic and social reorganization,” she wrote in 1922 (Parkhurst, 1922, p. 46). But she immediately adds that her ideas could also be applied to a much greater change, if they were not applied to the reorganization of an existing system, but to the organization of an entirely “new enterprise.”

A revitalization of the curriculum

“In this case it could be used for the carrying out of a freer curriculum composed entirely of projects set by the pupils themselves, and where the instructors would be regarded as consultant specialists” (Parkhurst, 1922, p. 46).

It took until the 1930s before Parkhurst herself realized that ideal, when her school in New York participated in the “Eight Years Study,” a large-scale research project involving 29 high-profile “progressive schools.” She then focused fully on developing an innovative curriculum, in which she did not see the curriculum so much as the entirety of learning content. She meant much more the integral concept of ‘programs of study’, which she saw as the vehicle through which the curriculum is transported and which ensures that students engage in their activities and makes working and learning more effective and efficient. For her, educational content must be meaningful, functional, and useful, and preferably lead to real-life experiences. She therefore opts for subject-integrated education (‘synthetic education’), which requires teachers to constantly be aware of the connections between learning content and working methods.

In the 1930s, Parkhurst developed programs for grades 9 through 12 that all included social science not as a subject, but as an integrating and overarching theme for all content (Progressive Education, 1943). Berends (2025) therefore states: “Parkhurst’s ‘any curriculum-can-do’ statement from Education on the Dalton Plan misleads us. In order to revitalize the ‘old school’, a different approach is needed first, but once that has been implemented, a change in the curriculum is also necessary.”

A pedagogical revitalization

Not only the curriculum, but also the pedagogical basis underlying the educational implications of the Dalton Plan was further developed by Parkhurst after the publication of Education on the Dalton Plan. The interviews Parkhurst conducted in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s were not unrelated to her earlier work at the Dalton School. Parkhurst sought forms in which children could reveal their way of thinking and feeling. Her aim was to give children a voice in their own lives and to help them help themselves.

Incidentally, Education on the Dalton Plan, published in 1922, also contains indications and building blocks that point to the revitalization idea being further developed in her later life. There are also indications of how the ‘why’ question in education can be answered, as well as how the curriculum as ‘programs of study’ can be improved by paying more attention to the pedagogical actions of the teacher.

[Taking charge of their own development]

[Taking charge of their own development]

Taking charge of their own development

Parkhurst wants to educate children to become ‘fearless human beings’ and believes that children should be given the space and taught how to take charge of their own development. She sees freedom and interaction of group life as two basic principles for this, as well as the principle of ‘budgeting time’. By this she means that children should learn to organize their own time.

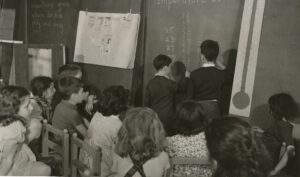

To achieve this, she lets children work on meaningful ‘assignments’ in ‘laboratories’. She advocates a form of experiential learning. She brings the world into the school and lets the children learn in the outside world too. This makes learning functional and meaningful. Parkhurst gives children the space to be entrepreneurial and to organize and plan their own learning.

To turn the school into a ‘sociological laboratory’ where children learn from and with each other and help each other, she also creates ‘houses’ where children can meet informally.